The idea behind this new feature is to give a little more background information and perhaps some slightly less well-known facts about our birds in the reserve - I hope you will find it interesting.

In addition to my notes below, why not check out the relevant page on the RSPB website, which contains some more information, drawings and videos and, most useful of all, recordings of songs and calls... www.rspb.org.uk

Blackcap | Black-headed Gull | Blue Tit | Bullfinch | Chiffchaff | Coal Tit | Common Buzzard | Cuckoo | Dunnock | Fieldfare | Firecrest | Goldcrest | Goldfinch | Great Spotted Woodpecker | Green Sandpiper | House Sparrow | Jackdaw | Jay | Kestrel | Long-tailed Tit | Mistle Thrush | Nightingale | Nuthatch | Redpoll | Redwing | Ring-necked Parakeet | Robin | Siskin | Snipe | Song Thrush | Starling | Swift | Treecreeper | Waxwing | Yellowhammer

34. Chiffchaff - phylloscopus collybita

The Chiffchaff is one of the archetypal harbingers of spring, and its simple 'chiff-chaff' song is one of the first signs that winter is over and brighter times are just around the corner. Normal arrival time in the UK is from about mid-March onwards.

This bird is a small warbler and first thing to say is that the whole subject of warbler identification is a bit of a minefield and can be quite intimidating for the inexperienced bird-watcher. Luckily the Chiffchaff is pretty easy - a kind of Warbler 101 - so a good place to start.

It is small - roughly Blue Tit sized, and a greenish brown above and off-white below, but colours tend to fade as the season progresses and the bird can become duller and more monochrome. There is a noticable pale supercilium (eye-stripe) and the bill is thin and dark and the legs are dark too.

The bird is insectivorous (small slim bill a dead giveaway) and will usually feed amongst the small, thin branches of trees such as willows and birches, and it builds a nest of grasses very close to the ground in overgrown verges etc, which are often a target for predators such as cats.

There are a number of confusion species, but only one is likely to be a real problem around these parts - the Willow Warbler, and these 2 species can best be differentiated by song.... The Chiffchaff is one of those helpful birds that says its name, with the song being a simple repetitive chiff-chaff (or zilp-zalp if you happen to be a German Chiffchaff - which is possibly an even better description of the song) whereas the Willow Warbler is a tuneful, descending trill which is quite different. There are also minor differences in physiology - the WW is supposed to have paler legs and a longer primary projection (that's the distance that the primary wing feathers stick out beyond the secondary flight feathers!) but personally I often find these features to be difficult to pick out in the field, as you are often looking up to see this tiny bird in silhouette.

A useful feature that does often work though, is that the Chiffchaff tends to flick its tail up and down a lot when perched or moving about through the trees and bushes... This is not 100% foolproof, as some WWs do too, so you can't really say that a bird that IS flicking its tail is definitely a Chiffchaff, but what you probably can say, is that a bird that ISN'T flicking its tail is most likely a Willow Warbler.

BUT, as I say, best bet is the song, which is a simple difference and (more-or-less!) foolproof.

33. Snipe - gallinago gallinago

The Snipe is one of the few waders that you stand a reasonable chance of seeing away from the typical coastal-marsh habitat which is the more usual haunt of this group of birds, and it has been recorded as a flyover in the reserve, but there are quite reliable populations of this species in the immediate local area at places such as Crowhurst and Blindley Heath, and large numbers at the Mercer's Park complex in Nutfield. In fact, in Winter 2012-13, over 70 Snipe were counted in one visit at Mercer's!

It is a bird of damp, boggy, rank grassland and the cryptic plumage means that this is not an easy bird to see. Luckily, it flushes very easily and will often fly off calling, when to hold its nerve and stay put would mean that you would probably never even notice it - having a dog does help in this regard, as the nervous Snipe will fly even more readily.

The plumage is a mixture of black, various shades of brown, and pale bars and stripes, with a distinctive stripey head. The most obvious feature is the very long, straight bill - which is used for probing for invertebrates in the mud - a dumpy body shape, with short legs giving a low, crouching posture. If not actively feeding, they will often sit immobile in the grasses, defying any predator to see them!

Calls are usually given when flushed and are typical of the explosive noise made by many waders - this one is often likened to the sound of a wellie being pulled out of squelchy mud! The most noteworthy sound though (and the reason for writing this piece at this time of year) is their display 'drumming', which is usually given in Spring-time, often at dusk. This is produced by the male spreading their tail-feathers out wide during their wild, diving display flights, which produces a kind of thrumming sound - difficult to describe, but very distinctive.

Confusion species are few: there is the Woodcock, which is a similar-looking bird but much larger, and also tends to favour damp, overgrown woodland rather than the wetlands of the Snipe, but also the Jack Snipe, and telling these apart is a bit more tricky....

The Jack Snipe is a bit smaller (and much rarer!) has a proportionately shorter bill and lacks the central pale crown-stripe of the Common Snipe, but the 2 best ways of telling the species apart are behavioural.... When feeding, the Jack Snipe has a kind of bouncing, backwards and forwards, rocking step (thought to disturb aquatic prey) and also, when flushed, it will not call and usually lands not far away, whereas the Common Snipe will flush calling loudly, and usually disappears into the far-distance.

32. Siskin carduelis spinus

Whilst on the subject of our winter migrants, I thought I might as well cover off the other bird which is most often see around these parts along with the Redpoll - the Siskin.

This is a very attractive small finch, which is quite canary-like in general appearance, and can quite often be seen in quite large numbers if the conditions and habitat are right - in Winter 2013, I have had a flock of up to 100 which have been resident in and around my garden, with the first birds appearing before Xmas and with 20+ still being present at the time of writing towards the end of March. In common with many winter migrants though, the number of birds visiting the southern UK varies greatly from year to year and is dependent upon food and climate conditions in their home range further north, and also food availability here. 2013 has been a particularly good 'Siskin-year' - unlike some years when it's hard to find any at all.

They are quite small - bring roughly the same size as a Lesser Redpoll or Blue Tit, and the overall colouration being a greenish yellow and black, with the males being particularly showy compared to the drabber females. The males develop a black crown, eye-mask and bib as they start to come into their breeding plumage and they have bold yellow and black stripes in the wing, which show well when in flight, a yellowish breast fading down to a streaked pale belly, and yellowish rump and tail-sides. The bill is a metallic grey with a darker tip and is quite long and pointed and the legs are grey. Females have similar colouration patterns but lack the sooty black parts and are overall a more greenish hue than the bright yellow males.

Food is predominantly small seeds of trees like pine and larch, but around these parts where those species are relatively rare, they are most often seen on birch and particularly alder. They will come readily to garden feeders and will take peanuts, niger seeds and sunflowers, and are often enticed in by Goldfinches, with which they often form mixed feeding flocks. As mentioned, they can be very sedentary and will stay in one place as long as there is a ready supply of food - the ones in my garden seldom venture out of the immediate local area.

They can be surprisingly hard to see and are one of those species that can seemingly hide behind the smallest obstruction, so a suitable tree can often appear to be empty, and it is quite a surprise when a flock of Siskins suddenly get flushed away. Luckily, they are rarely silent and their twittering contact calls will usually alert you to their presence, and this is the signal to start looking - carefully!

Their breeding territory is typically in spruce and pine forests of northern Europe including the northern parts of the UK. They were not considered to be breeding birds of Surrey until a few pairs have been found to remain all year round in recent decades - I am quite interested as to when the biological imperative will overcome the ready supply of sunflower hearts, and they abandon my garden.

31. Redpoll carduelis flammea

When I say 'Redpoll', probably the first thing to point out is that I am actually referring to the Lesser Redpoll - there are several species and races of Redpolls, and few groups of birds create as much confusion, with their various latin and common names - but the species most likely to be seen around here is the Lesser Redpoll, and that is the one that we will concentrate on!

They are primarily a winter visitor around these parts, as they tend to breed further north in the UK and also northern Europe. I have actually seen them here in the summer - I suspect small numbers may breed in places like Ashdown and Worth Forests but, much like Siskins, a bird which which they often associate, it is as a winter visitor that we are most likely to see them.

They are small (roughly Blue-tit sized) streaky brown above with a paler buff chest and belly. The head is streaked, and they have a small red spot on their forehead which gives them their name. The males develop extensive red chests in the spring-time, as they start to get their breeding plumage, at which time they can be very attractive indeed. The small triangular bill is yellow and they have a small black bib below, and they also have a paler wing-bar, which is almost white in adult birds. They are quite hard to find and photograph, and my pic below is pretty poor, but there are some better images readily available on the internet, which will do better justice to this beautiful bird.

The call is mainly a harsh, metallic sounding chett, chett, but best to listen to the recordings.

This is a very unobtrusive bird, and you can be quite close to a large flock of these and not know it! They feed in the upper branches of trees such as alder and hazel, but their small size and mainly drab colouration means that they can effective 'disappear' very easily - careful examination is required of any small birds seen at the top of such trees in winter, and you may well find that you have stumbled on a large-ish flock. They will sometimes also feed on seed-heads of flowers and weeds, and this is a good reason to leave tidying up of these until the spring, as it is by no means impossible to attract Redpolls into your garden in the winter by leaving things such as lavender to go to seed.

30. Waxwing bombycilla garrulus

There can only really be one candidate for 'bird of the week' this week, as the sighting of a flock of Waxwings in the reserve is a fantastic event - this species has it all really, being a very attractive bird but with scarcity value as well, and this is the first time that they have been recorded on the reserve.

They spend most of the year in the coniferous woodland of Scandinavia and Russia, and are an annual visitor to northern UK which they visit to escape the worst of the continental winter and to mop up any berries that are left in our own country. Every few years, this annual visitation comprises far larger numbers of birds than usual, and they will sometimes move south and west throughout the whole of the UK in an effort to find food, giving everyone a chance to hunt for this rare and exotic visitor during so-called 'Waxwing-winters'.

The last one of these was in 2010, but they are here again this year and several sightings have occurred in the SE and also the immediate local areas.

Unfortunately, berries are thin on the ground here in the UK this year, but Waxwings have one big advantage over other berry-seekers, such as thrushes, in that they are quite happy to go into gardens, towns and cities to seek out food, and one of the most common places to find a flock of Waxwings in on the ornamental trees and bushes, such as rowans, berberis and cotoneaster that are frequently used to spruce up places like street verges and supermarket car parks. Once Waxwings find a source of food, they will usually stay in the area for days or weeks, and will return time after time until all the berries have been exhausted. They are also drawn to things like windfall apples in orchards and gardens, so it may be worth hanging up some apples if you know that Waxwings are in the area. There is some spectacular footage of Waxwings feeding on apples from the hands of a young lad up in the Scottish islands - although I wouldn't hold my breath waiting for that to happen!

In appearance, they are unmistakeable, being roughly Starling-sized and with an overall pinkish-buff colouration, a rakish crest and black 'bandits-mask', white and bright red patches on the wings (hence the name!) and yellow, black and white stripes on the primary wing feathers and a yellow band across the tail - wow!

In flight and when perched up, their overall size and body shape is reminiscent of Starlings, but their pleasant, bell-like, tinkling calls are very unlike the whirrs, whistles and tweets that Starlings make, so a useful differentiator if you see a flock perched up on a tree-top somewhere, and Waxwings will usually call as they arrive to feed, so a good signal of their presence.

An A++ species!!

29. Starling sternus vulgaris

The Starling is another of the bird species whose numbers have been dropping in recent decades, and the vast winter flocks that used to be seen are now far more difficult to find, although there are still traditional roost-sites, such as the Somerset levels and Brighton pier, where the spectacle of many thousands of birds wheeling about in the dusk sky can still be enjoyed.

This species is resident in the UK, but numbers are greatly increased in winter, as our own birds are joined by visitors from continental Europe.

They nest in holes and crevices, and a good place to find them in Spring-time is Headland Way, where the tiles that have been used for many of the roofs seem to be exactly of the right size and shape to afford plenty of nesting sites for Starlings, and the noise of many nests full of young birds, all crying out for food, can create quite a clamour. They will eat most things, including invertebrates, seeds and berries, and the newly fledged youngsters will join the adults to make sizable feeding flocks as they seek out their favourite prey - Cranefly larvae (leatherjackets) - in the Spring. By closely watching the birds along my road, I have noted that they are happy to start off a second brood of young immediately after the first has fledged.

Seen well, Starlings are very handsome birds, with their irredescent green and purple plumage, attractive spots and yellow bill, and they make a distinctive 'delta-wing' shape when seen in flight. The adult male can be identified by the blue-grey base to the bill, whereas the female is more yellow-white.

There aren't really any confusion species in the UK, but in mainland Europe there is another similar species called the Spotless Starling - which is similar except in one regard!

I have been meaning to go and check, but last Winter there was a large (4000+) flock which gathered to roost in the reeds at Hedgecourt Lake, and they made quite a spectacular sight as they swooped round and round the lake in preparation to zooming into the reedbeds to spend the night, where they would be safe from predators.

28. Robin erithacus rubecula

What more Christmas-y bird could there be than the Robin! Unfortunately, I have never been able to get the archetypal photograph of a bird sitting on a snowy branch, but at least I've got one that is OK for showing the salient features.

It has warm brown upperparts and an olive-buff underside which can become almost white towards the belly, particularly in winter, quite a small fine dark bill and a large dark eye. The red 'breast' is interesting, as a cursory glance will show that it isn't just the breast which is a vivid orange-red, but the whole of the breast, neck and face - millions of school-children have been drawing them wrong for all of these years! Males and females are hard to tell apart - although presumably not to other Robins!

Robins like to sing and have quite a loud, musical song which is often given from a prominent perch and they will sing all year round, pausing only to keep a low-profile for a few weeks when they are moulting. The alarm call, which you will often hear coming from a dense bush or hedge is a sharp 'tik'.

They are a bird of woodlands and, increasingly, gardens - but if you think you have a Robin in your garden all-year-round, it is likely to actually be a number of different birds. Our British birds tend to move SW in the winter and are replaced by visitors from the near continent and Scandinavia. Outside of the breeding season, they are extremely territorial and aggressive towards other Robins and will squabble incessantly. I have seen one go apoplectic with rage, as it tries to 'see-off' a rival in the wing-mirror of a car!

Robins will eat seeds etc and will mop up spillage from bird feeders, but their main diet is insects and they will faithfully follow a gardener to 'help' by dealing with invertebrates that have been uncovered by digging - thus giving rise to the other archetypal Robin photo - sitting on a spade-handle. Robins are also quite easy to 'tame', and will come to cheese and scraps so readily that they will feed out of your hand. I have heard it said that it is only our British Robins that will be so confiding of human presence, and that it is usually quite a shy and retiring species across most of its range.

The Robin is a good bird to practice on if you want to try to get to grips with a bird's 'jizz' (ie the innumerable small features, behaviour etc that identify a particular species).... Anyone can identify a Robin by looking at the red breast, but what if you can't see that particular feature.... Robin's can quite easily be identified by their warm brown colouration, dumpy shape and upright posture, plus legs that look impossibly thin. If your brief view is of a bird that you have flushed, then it would almost certainly have been flushed from on or near the ground, and it will fly off low, until doing a final swerve with an upward kink to get to a new hiding place not too far away - easy!

27. Treecreeper - Certhia familiaris

Partly in celebration of the fact that we now have this species using one of our new nestboxes on the reserve, and partly to give us all a break from thrushes, I thought I would branch out and tell you about one of our more unusual species that we sometimes see in the reserve.

English names for bird species are not necessarily all that descriptive of the appearance or habits of the bird concerned, but not in the case of Treecreeper, since that is a very apt description of what it spends most of its time doing. Like the Nuthatch, it is a bird that likes to spend its time hunting for insects in the gnarled bark of mature trees, but unlike the Nuthatch (which usual starts high and works downwards) the Treecreeper starts low and works upwards, and then flies down to start at the bottom of the next tree or branch.

It is when it is flying that it is sometimes easiest to see, as the cryptic mantle plumage offers excellent camouflage as it creeps its way, mouse-like, up the tree branches and trunk. When flying to a new tree however, the white chest and belly plumage flash out quite brightly and will draw the eye in a dimly-lit wood.

Along with several other interesting species, the Treecreeper sometimes associates with feeding tit-flocks in the winter, and will often be one of the ones at the back, so always worth a look.

Another good way of spotting this unobtrusive bird is by its call, which is a high, thin, indrawn sreeeee, which is difficult to describe, but quite characteristic, so have a listen on one of the web-sites and you will by surprised at how often you hear it in the woods, but unfortunately, actually seeing the bird is often more of a challenge!

There aren't really any confusion species other that the Short-toed Treecreeper, which luckily is seldom seen in the UK - I say luckily, because the 2 species are extremely hard to tell apart, being only differentiated by subtle plumage differences (plus the length of their toes - well actually the hindclaw - of course)

We are quite honoured to have them nesting in one of our boxes, as the more usual site is just to build their neat, grassy nests behind a piece of bark or wood that has lifted away from the main trunk.

26. Fieldfare - Turdus pilaris

This is the last of the common thrushes that we see in the UK, and also the most attractive. So much so in fact, that the Spanish call this zorzal real or Royal Thrush!

It is a large thrush, being closer in size to species such as Mistle Thrush or Blackbird, rather than the smaller Redwing or Song Thrush, and has extremely distinctive plumage features, particularly in the spring-time when the birds are coming into their bright breeding colours prior to making their way back to their breeding territories in Scandinavia and the north.

They have a blue/grey head with a black mask through the eye and a paler stripe above, and the bill is a striking yellow and black. When seen at rest, the mantle (back and wings) is a plainish dark brown, the flanks are pale with large, dark crescent-shaped spots and the orange-tinged breast leads up to a pale throat. It is only when seen in flight though that some of the plumage features really show out, with the almost black tail contrasting sharply with the pale grey rump, and the plain white-ish belly contrasting with the orange-tinged and spotty breast.

The call (which they do a lot!) is very distinctive too, being a chicken-like 'chuk, chuk, chuk', which carries well and can often be the first indication of a flock of Fieldfares passing high overhead.

They have been arriving in the UK over the last few weeks in a bid to escape the harsher northern winters, and will stay here until well into the spring. Late birds are sometimes recorded into May but they usually start to make their way back from about late March.

Along with other thrushes, the Fieldfare will probably not have an easy time of it this winter, as natural fruiting plants have done poorly in northern Europe this year, so we are expecting a bumper crop of thrushes to come here - only slight snag being that the fruit harvests here have been poor too, with both natural foods such as sloes, hawthorn etc as well as apples and pears all fruiting rather badly.

A good way of getting Fieldfares and other thrushes into your garden is to hang up apples, and I imagine that this supplementary food will be very welcome this year, particularly as the cold weather sets in and other food such as invertebrates become hard to find. A good place to find Fieldfares - as well as more exotic species such as Waxwing - is feeding on windfalls in orchards. Not quite sure how this year will go, as apple harvests have been poor, but the orchards at Crowhurst Place usually hold a flock of a couple of hundred Fieldfares and Redwings.

25. Redwing - Turdus iliacus

Continuing the thrush-theme, I thought I would introduce the first of our 'winter' thrushes - the Redwing - as these have just started to appear in the area in the last week or so.

In terms of size and general appearance, Redwings are quite similar to Song Thrushes, but have a couple of obvious differences - the first gives them their name, and is large, russet-red patches on the underwing coverts or 'armpits' but, whilst these normally show well when the bird is in flight, they are sometimes covered up when the bird is at rest or feeding. The second difference is always visible, and that is the pale stripes both above the eye and as a 'moustache' which enclose a dark cheek patch - this contrasts very well with the rather plain-faced Song Thrush.

Thrushes are not fussy as regards food and will take a variety of invertebrates and seeds, but will also take fruit and berries - this latter food becoming particularly important when the ground is frozen or snow-covered, and one of the best ways of attracting thrushes into your garden is to hang apples up in very harsh weather, when the birds are struggling to find any natural food.

The Redwing is a winter visitor to the UK, being driven from their Scandinavian homelands by the onset of harsh weather in the autumn, they sweep across the UK in a southerly and westerly direction, and will gather in large flocks if the conditions are to their liking. Their flight call is a thin single-note 'seeep', but they will often 'chatter' when gathered in large feeding flocks in the woods, and sound quite a bit like a flock of House Sparrows.

It is lack of food in Scandinavia that drives the Redwings (and other species) to search for milder feeding conditions in places like the UK, and early indications are that this year will be a bumper year for such migrants, as they are already being noted in very large numbers. This is because much of near-continental Europe has had an awful year for fruits and berries, with many species such as acorns, beech-mast, sloes and even apples having fruited very poorly. Only slight snag for the migrants is that we are no better off here in the UK, so it may well be a case of many birds competing for not much food, so it will be doubly important to feed the birds in our own gardens this winter - particularly if the trend of harsh winters that we have been experiencing these last few years were to continue. It would also be a great opportunity to see a handsome Redwing, Fieldfare or maybe even an over-wintering Blackcap at close quarters.

24. Mistle Thrush - Turdus viscivorus

I thought that, whilst on the subject of thrushes, I might as well complete the set, and tell you about the other spotted thrush that we get here in the UK - the Mistle Thrush, plus I'll add in the Redwing and Fieldfare a bit later on in the autumn, as they will be arriving here in the UK any time now and will spend the winter.

Mistle Thrushes are our biggest thrush, being significantly bigger than the Song Thrush and even a bit bigger than Blackbirds. They are basically a drab grey-brown above, paler below and have a large dark eye in a plainish face. The spots are more like dark irregular blobs (compared to the arrowheads of the Song Thrush) and sometimes give the impression of joining up to form darker patches. As compared to the Song Thrush, overall impression is a bird which is slightly greyer and colder toned.

They are few and far between these days, but if you do see them, it is usually on the ground feeding in shortish grass, and almost invariably in pairs. They are quite big and stand tall, with their thin necks almost giving the impression that they are craning their heads. In flight, they usually have long glides between flurries of wing-beats, and so are quite reminiscent of woodpeckers. Sometimes in the autumn, they gather together in larger extended family groups, but it's been a good few years since I've seen this! Chances are, you won't see one in your garden.

They have been recorded on the reserve, but not by me. One place that you have quite a good chance of seeing them is in the parkland between the station and racecourse as there is often a pair there, but they are sadly quite rare these days, so good luck!

They are resident in the UK all year round, and they don't really migrate, although a few birds from Scandinavia and Scotland sometimes come a bit further south in the UK to escape bad weather.

They will feed on most insects, but don't bash snails like Song Thrushes do, but are extremely territorial about fruit-bearing trees and bushes, often seeing off all-comers and saving the bounty for themselves for as long as it lasts. As the name suggests, they like mistletoe berries, but there is no evidence that the lack of Mistle Thrushes and the lack of mistletoe around these parts is linked.

The song is a wistful fluting, a bit like a simple version of a Blackbird song, and the alarm call is a machine-gun rattle - some say a bit like a football rattle. They also like to sing at night, particularly if there is bad weather in the offing, which gives them their old country name - Stormcock!

23. Song Thrush - Turdus philomelos

The Song Thrush is one of the 3 most common thrushes which are resident around this part of the world all-year-round.... although you might be forgiven for wondering about this, as I can't think of another species which is so common and visible at some times of the year, and yet so skulking and secretive at other times that you would be forgiven for thinking that they aren't there at all.

One of the most common indications of the presence of this species is the song, which is a thing of wonder (hence the name!) and it is just about the dominant singer in late winter and early spring as the males start to establish their breeding territories and attract females. The song is extremely varied, but luckily has some distinctive characteristics which make the Song Thrush very easy to identify. First thing is that the song is extremely loud and far-carrying - I remember standing on the reserve last February and being able to hear 5 different males all belting it out from the tops of tall trees (a favourite singing location) in the vicinity. The other thing that makes their song unique is that it is always very short phrases of song - usually only 1-4 notes - but each phrase is always repeated, usually 3 times but sometimes more if it is only a single or double note.... It is almost as if the bird is saying to itself "Did you like that? Want to hear it again?" The single note alarm-call is also distinctive, and is often the only indication of the species, as it sees you coming and flushes away out of sight.

Unfortunately, outside of their main period of breeding activity, Song Thrushes are much harder to see. They are fairly small (being only about halfway between a Sparrow and a Blackbird) with nondescript brown plumage and a quite skulking habit. They are most often seen along the edges of hedges or woodland, where they usually feed on the ground. In winter, they can often be seen turning over piles of leaves in the hope of finding their insect prey, and they are also the gardener's friend, in that they like to feed on snails, which they bash repeatedly on an 'anvil-stone' until they can break through the shell and get at the snail inside. Like other thrushes, they are also fond of fruit and berries and will come onto lawns etc to feed on wind-falls, although the thrushes as a group are extremely possessive of such food-sources, and the smaller Song Thrush will often be sent packing by the larger and more aggressive Blackbirds and Fieldfares. They tend not to come to bird-tables much, but will sometimes try to mop up the spillage of seeds left by other birds. In my experience, if a bird 'adopts' your garden, they will often stay for long periods throughout the winter.

When lacking anything to give an indication of relative sizes, it can sometimes be surprisingly hard to differentiate the Song Thrush from the other spotted thrush, the Mistle Thrush. This latter species is much larger, but size is not always easy if you can't see both species together, but the Song Thrush has spots which are usually quite evenly-spaced and are each arrow-shaped. The spots of the Mistle Thrush are a bit larger and darker irregular 'blobs' and are a bit more unevenly spread, so sometimes give the impression of merging into darker patches.

The BTO have just started a winter-long survey of all of the thrush species, so our own plus the winter migrants of Fieldfare and Redwing (plus the extremely rare Ring Ouzel) and I am taking part in this, so it will be interesting to get a wider perspective of how the birds are getting on. I do get the impression that both Song and Mistle Thrushes though are in decline. Bit difficult to tell with Blackbirds, as we have many of our own, and the numbers are boosted by many migrants from Scandinavia in the winter.

22. Yellowhammer - Emberiza citrinella

The Yellowhammer is one of the most handsome and emblematic birds of the British countryside, but sadly yet another one to add to the list of species that aren't doing very well.

We had only a very few sightings in the reserve this winter, and no breeding evidence at all, so I'm afraid that it is likely that falling numbers has meant that they are no longer being attracted to the reserve, which has a good deal more human disturbance than most of the surrounding countryside, where the birds can still be found in small (and falling!) numbers. I have a colleague who monitors the birds around the N Downs area, and he has noted that Yellowhammers have now died out from most of his area, with no birds at all on Riddlesdown Common any longer, which has been a stronghold for the species for several decades. It is the usual story of poor land management (from a bird's perspective) and too much human disturbance.

With one exception (more on that later!) they are very easy to identify, with their bright colouration and characteristic song - males in particular being very impressive. They are of an overall yellow colour, particularly around the head and throat area, and have the stripey head that are seen in many bunting species. The males in breeding plumage are impressive, with a bright yellow head, chest and belly, and rusty-red and black barrred wings. The tail corners are white and can often flash quite visibly as the bird is in flight, and the rump is a rich chestnut-brown. This distinguishes the Yellowhammer from its only potential confusion species - the Cirl Bunting - which has a olive-green rump. 'Luckily', the Cirl Bunting is extinct in the UK apart from some small colonies in Devon and Cornwall - the last ones around these parts died out in Sussex in about 1970 - so the chances of seeing one to get confused about are not very high.

The song is very distinctive, being the famous 'Little piece of bread but no cheese.' of country legend. This is a good way of remembering it, but not very accurate... It is actually more like a series of buzzing single notes, followed by one extended one that is usually 2 long syllables ending on a down-slur. Much more useful though is to learn the contact call, which is a just a single buzzy note, which carries surprisingly far, and is very often the first indication that the species is in the area.

Food is some insects but mainly seeds, which is their big problem, since winter seed is fairly hard to come by these days, and this species does not come to birdfeeders. I'm not quite sure how they do it, but when they do find an area with good winter feeding, they gather in quite large groups to all feed together. I have seen groups of 100+ together on a number of occasions, which must mean that all of the birds for miles around have somehow gathered in one place.

21. Green Sandpiper - tringa ochropus

It might seem a bit strange to be featuring a wader as 'bird of the week' on our little inland reserve, as they are far more often seen on or near the coast, or at the sides of large lakes and pits, but nonetheless, we do have Green Sandpiper on our reserve list, and if ever another wader is going to seen on the reserve, then now is the time of year, as both fresh juveniles and returning adults will sometimes stop off at unlikely places as they return from their breeding grounds in the North.

The mere mention of the word 'wader' is often enough to send a shiver down the spine of many (even quite experienced!) birdwatchers, mainly due to difficulties in identification.... There are quite a few species to be seen in the UK, and they are often quite superficially alike, plus they are often seen in poor light and at long distances, so telling one species from another can be a bit of a challenge; but as usual, with a bit of patience and attention to detail, it is normally relatively straight forward to separate the species - or it is unless you get involved with rare US vagrants anyway!

One of the main 'features' that makes it easy to identify a Green Sandpiper is its lack of features! .... it is basically a dark greenish-grey above and a dirty white below, with no significant head-markings, dirty greenish legs and mid-length, straight dark bill. If you can get close enough (or have a telescope handy!) then it is possible to detect small white spots dotted around the darker mantle plumage, and this is diagnostic of the species.

They are quite small, being roughly Starling-sized, and would often be seen in twos or threes (although not if one were ever to turn up on the reserve again I suspect) and will feed by quietly probing for small invertebrates along the muddy shallows. One of the most frequent views that you will get of this bird, is when you have just unknowingly flushed it from its unobtrusive feeding along the water's edge, and it explodes upwards with a loud ringing, whistling call which is given as it disappears very rapidly, but giving obvious views of its clear, white rump.

The photograph below is rather untypical of the usual view of this species, as this is an adult male in full breeding plumage - which means that the white spots are a lot more obvious and the neck plumage is much more mottled than the more 'black and white' juveniles, which are by far the most likely to be seen around these parts.

Anyway, I hope you have enjoyed this brief glimpse into the rather exotic world of the wader - they are a bit of a challenge, but some of our most beautiful birds come from the waders group.... They're extremely unlikely to ever show up on our reserve though, so I just need to figure out some way of coming up with an excuse for sharing the photographs that I have.....

PS. Sorry about the quality of the photograph.... This would have been taken at quite some distance!!

20. Coal Tit - parus ater

To the untrained eye, it is sometimes surprisingly easy to confuse the Coal Tit which is in your garden with the flock of Blue Tits - but a more careful look will show that the 2 species are not really very much alike at all.

First big difference is overall colouration - whereas the Blue Tit is basically a blue and yellow bird, Coal Tits have no trace of either of these colours and are black and white on top, with a buff-coloured chest and belly. The pattern of colouration though is quite similar, so I guess you can see where some confusion might arise. Another diagnostic feature is that the Coal Tit has a large and very obvious white patch at the nape of the neck.

The Coal Tit is also a bit smaller than the Blue Tit - so that's what you are looking for..... a smaller, more monochrome version may well be a Coal Tit.

In Winter, Coal Tits will join up with other species to make large flocks that will forage through the woods on joint feeding parties, but at all other times of the year, they are mainly confined to conifers, where they will often take advantage of their tiny size to hunt for insects and seeds on even the thinnest of branches. They are most common in large expanses of conifers but can also be seen where only a few exist - we occasionally have Coal Tits in the reserve and I sometimes see them on my feeders - I imagine that they are able to make a reasonable living in the area due to the number of ornamental conifers that people have planted in their gardens.

They will come to feeders, where another difference can be seen to the other Tits. As Coal Tits are so small, they are often bullied away from the food by other species, so they usually don't stop to eat there, but rather ferry seeds and nuts away to a secret stash where they can eat them with less disturbance later.

Many of the Tit species have quite a range of calls, peeps and song, and the Coal Tit is no exception. I find that it is easiest to pick out by tone-of-voice, which is surprisingly strong for such a small bird - bringing to mind the calls of Marsh Tits rather than Blue Tits.

I'm not aware of any definitive studies, but my impression is that Coal Tits are not doing very well. In mixed woodland and gardens the best you will ever get is the occasional sighting - it is in larger areas of coniferous forest that you would expect to find relatively large numbers of these birds, and my impression is that you don't see so many these days. I went for 3 walks around Buchan CP (nr Crawley - which is just such a habitat) last Spring, and I was quite surprised at just how few Coal Tits I noted. Being so small, they are vulnerable to the weather, and I wonder if they are suffering a bit in the comparitively harsh Winters that we have been having these past few years.

19. Bullfinch - pyrrhula pyrrhula

For a bird which is so brightly coloured - particularly the males - Bullfinches can be surprisingly hard to spot. They are usually quite shy of human presence, and are one of those species that are invariably 'on the other side of the hedge' so it is important to learn their call, which will often alert you to their presence in the area, and you can then pause and have a good look, in the hope of getting a glimpse.

The main call is a soft, indrawn, melancholy (and rather pathetic sounding) single or double note 'phiiii' or 'phiiii, pheew' (best bet is to listen to it on one of the internet sites!) and is pretty-much unique and quite distinctive. Once you have got the hang of it, you will be surprised at just how many Bullfinches are in the area, and in the LNR, we have at least a couple of pairs all-year-round, and they are joined by several others in the winter months, as they particularly enjoy the berries down in the pond-enclosure.

The males are very showy, with a bright pink breast and belly, black wings with a broad white bar, dove-grey back and black tail. The head has a black hood and the short, triangular bill is a dark steely-grey. One of the best field marks, which is always very visible when the bird is flying away from you (which they often are!) is that they have a large, and bright-white rump-patch. The females are quite similar in most plumage details, but the pink breast is replaced by a buff-coloured breast which has only a hint of smoky-pink about it. During the period late-Winter - Summer both male and female will associate closely together, and you will usually be able to see both sexes for comparison. In the Autumn and early-Winter, they will often gather in small groups to feed on a patch of berries, and will haunt the same area for weeks or maybe months at a time, as long as the food holds out.

In the case of the reserve, good places to spot them are the pond-enclosure (all year round, but particularly in the Winter) and they seem to like the thick hedges in the Wildflower Meadow and have nested there in each of the last 2 years.

Food is mainly berries, shoots and a particular favourite is fruit-buds, which led to a very sticky patch for the Bullfinch, as they were once quite numerous, and considered to be a pest by fruit-tree growers and as late as the 1970s, they were still being actively persecuted with a bounty on their heads. Records still exist showing numbers of Bullfinches that were killed, and in happier times when we had a much higher general bird-populations in the UK, records show bounties have been paid for thousands of birds in some individual parishes over a period of years. Even the Protection of Birds act of 1954 made specific exclusion of Bullfinches and they were still actively persecuted after that time. They do enjoy some protection now, and numbers are starting to recover a little bit, and like many other species, they are now starting to learn the knack of taking advantage of our garden feeders.

If you are interested in reading a bit more, have a look here which is a typical tale of what happens when wildlife comes into contact with human commercial activity.

18. Black-headed Gull - larus ridibundus

The first thing to say about the Black-headed Gull is that it hasn't ever really got a black head! It is one of the 'hooded' gulls, which develop a dark hood over the head and nape, but only during the breeding season, and even then, in the case of the Black-headed Gull, the hood is actually a dark chocolate brown. Just to add to the confusion, there is a gull species which actually does have a black hood, but that is the Mediterranean Gull, and they are relatively rare inland in the SE UK. For all of the rest of the year, the black hood isn't present, but the Black-headed Gull does have another handy field-mark, in that in all other plumages, it has a dark spot just about where you might think the ear should be - you can see this clearly from my photograph, which is of an adult bird in non-breeding plumage..

Identifying gulls is generally a bit of a nightmare - not least because they are often seen at some distance - but the B-h Gull is relatively straightforward due to its small size (the smallest of the common UK gulls around these parts) its mid-grey back and wings, the orange red legs and bill, and (best field-mark in flight) the white leading-edge to the outer wings.... This combination of field-marks is unique to this species.

It is a gull which is doing very well in the UK, and is no longer confined to coastal areas but will congregate on lakes and pits, refuse tips and will gather from far and wide to follow a plough. Funnily enough, we get very few of them in the immediate local area (I remember it took me about a year to add them to my local list when I first moved to Lingfield) but there are usually a few to be found at Hedgecourt lake and, less often, the Wire Mill.

They are gregarious birds, and will often gather in large noisy groups and will eat just about anything, from worms, seeds and fish and will even 'hawk' for insects in flight.

17. Kestrel - falco tinninculus

The Kestrel is one of our smallest birds of prey, but one of the most easily recognised. It is a member of the falcon family (like Hobbies and Peregrines) and has the typical falcon-shape - long, slim wings and a generally lighter build than other potential confusion species such as the Sparrowhawk.

One of the reasons that Kestrels are so well known is their habit of hovering over roadside verges - these being very fertile ground for the mice and voles which form an important part of their diet - and there was once a time (maybe 15-20 years ago) when no motorway journey could be undertaken without seeing numerous Kestrels at close quarters. There are far fewer Kestrels seen doing that these days, and the reasons are not exactly clear.... maybe the motorway verges are being more actively managed and have fewer rodents, maybe there are more rodents in set-aside strips in the wider countryside, or maybe there are just fewer Kestrels!

This latter point is causing some debate in bird-watching circles at the moment - from being our most commonly seen bird of prey perhaps 20 years ago, the feeling is that the Kestrel has been supplanted by Buzzards and probably Sparrowhawks, but I do wonder whether the situation is quite that black and white, as birds of prey are sometimes difficult to identify by species, and also quite secretive about their nest-sites, and it may just be that there seems to be far fewer Kestrels as they now seldom use motorway verges!

Anyway.... male and female Kestrels (unlike many bird of prey species) are roughly the same size, and the best field mark is their rich chestnut brown back and inner wings - this can usually be seen quite easily when they are in flight, and enables this species to be quite easily separated from other potential confusion species, such as Sparrowhawks or Merlins. In both sexes the outer-wings are dark (almost black) but the male has an additional blue-grey panel towards the rear of the inner-wings. The male also has a blue-grey head, unlike the female which is brown all over, plus the brown back is heavily streaked in the female but plainer in the male. When seen from below, the long tail has a dark terminal band. The legs and eye-ring are a bright yellow.

The photograph below is of a female.

The Kestrel is the only small UK bird of prey that can hover, and this is how they are most often seen - with their tail spread wide and their wings beating rapidly to hold a stationary position in the air, as they scan the ground below for food.

Favourite food is rodents, but they will also take insects, lizards and small birds - I have a photograph of a large female Kestrel which has just killed a Starling - but voles are the food-of-choice.

They will nest in a variety of places, from cliff-ledges, to old buildings, to abandoned corvid-nests, through to tree holes, but as mentioned, the nests are usually quite hard to find!

16. Long-tailed Tit - aigithalos caudatus

The Long-tailed Tit has got to be one our cutest and most charismatic birds - with its long tail and tiny round body, it resembles nothing so much as a flying lollipop!

In colouration, it is mainly pink and black, with a pinkish-buff chest and belly, with a pale central crown stripe and black area above the eye, and then white cheeks. It has dark legs and a tiny black bill, which reflects its usual diet of tiny insects and seeds.

The call is a quite distinctive buzzing srrii, srrii, srrii which the birds utter constantly as they move about feeding.

One of the interesting things about Long-tailed Tits is the way that they flock together at different times of the year. In early Spring they are starting to pair up and are usually just seen in 2s as they quietly go about finding a territory and building their nests (more about those in a minute!) and they are usually at their most unobtrusive at this time of the year. Once the young are out of the nest by late Spring/early Summer, they stick together as a family group and start to become much more obvious, and then as Autumn comes and throughout the Winter, several family groups will form together to form a large feeding flock of typically 15-30 birds and become very noticeable as they move through the woods.

From late Summer through to early Spring, many woodland birds form into large mixed feeding flocks (it helps them to find food by going mob-handed) and the Long-tailed Tits are usually in the vanguard of these groups. It is very predictable actually, with Long-taileds leading the way, followed by Blue and Great Tits, with the real 'goodies' bringing up the rear, and one of the best ways of finding birds such as Marsh Tits, Nuthatches, Treecreepers, Goldcrests and even over-wintering Chiffchaffs is to locate a feeding flock of Long-tailed Tits by their calls and position yourself in their path, so that they all stream slowly past you, as they work their way through the tree branches looking for insects etc. In another endearing feature, Long-tailed Tits are very accepting of a non-threatening human presence and will come down very close to you, particularly if you can cheat by impersonating their simple clicking contact call - I don't suppose for a moment that they are fooled into thinking that you are actually a funny-looking, giant Long-tailed Tit, but they just can't seem to help themselves from coming and having a look!

Back to the nest.... It is a small, rugby-ball shaped sphere, which is largely made out of moss and lichens, which they cunningly glue together with spiders' webs. When first built and used, it is quite small - maybe a bit bigger than a tennis ball - but as the young grow bigger inside, the nest is built in such a way as to be able to expand to accommodate the growing chicks. Very clever!

There may be more - they can be surprisingly quiet and sneaky during the breeding season - but I know we have at least 2 nests on the reserve.

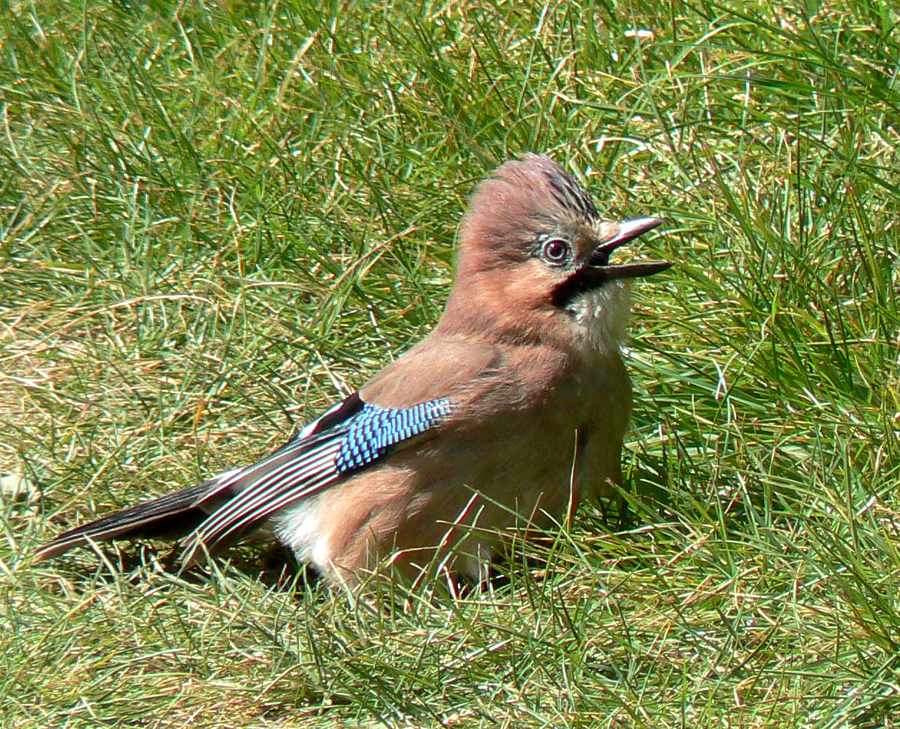

15. Jay - garrulus glandarius

The Jay is the most colourful member of the corvid family (ie crows) but is really quite unmistakeable with its pale, pinkish-grey body, black and white head, jazzy raised crest, and irridescent blue panel on its wings, which is more easily seen when the bird is at rest. In flight, the wings appear mainly black and white and the tail is black, but the most obvious field-mark (particularly when the bird is flying away from you - which they often are!) is a very large and bright white rump patch, making the Jay appear like a giant Bullfinch!

You might think that the combination of colours would make the Jay unmistakeable, but I have a friend who is 'chief identifications officer' for the local RSPB group, and he tells me that the Jay is responsible for more erroneous 'sightings' than any other species, with any number of people having contacted him to report that they have a Hoopoe in their garden!

It is chiefly a bird of woodland, but can also be seen in parks and gardens, and we have at least one pair who are quite often seen in the reserve. I'm not aware of any definitive studies, but my own impression is that Jays are doing rather well - at least I seem to see rather more of them about these days than in years-gone-by.

Like many corvids, they will eat just about anything, but they are most famous for eating acorns - in fact one of their old country names is the Acorn Jay and they will collect, and often bury for later, thousands of acorns during the autumn - most of which they will remember and return to eat in harder times, but some of which will get missed, and so the Jay is an important dispersal method for oak trees.

The most usual call is a harsh screech, which sounds a bit like cloth-ripping, and this is often the first indication that you might get to the presence of this bird as you go walking through woodland. However a much rarer call is that they can do a perfect impersonation of the call of a Tawny Owl (the too-witt, too-whoo) and my own personal theory is that they are responsible for most of the day-time reports of calling owls!

Jays are one of the species which enjoys 'anting', which basically consists of stirring up an ants-nest and then sitting in it! The theory being that the angry ants will start spraying formic acid around, which will help the Jay to get rid of parasites. It's quite amusing to watch them doing this, as they seem to become quite pre-occupied with what they are doing and take on a kind of wistful expression and will allow a mush closer approach than usual - the photograph below shows a bird 'anting' in the Community Orchard, and I was able to creep up to within 10feet or so before it eventually flew off!

14. Goldfinch - carduelis carduelis

The Goldfinch is one of the most attractive and colourful of our year-round residents. It has a black and white head and extensive red to the facial area, the back is an olive-green colour and a paler chest and belly, with mainly black wings with a very broad yellow stripe, which gives the bird its name, as this yellow stripe flashes very brightly when the bird is seen in flight. The bill is very long for that of a seed-eating bird and the length of it plus the pointed end gives a clue to the fact that this bird's diet is mainly small seeds, such as teasel or thistle, rather than the bigger ones favoured by other stronger finches and sparrows.

In some ways, the exotic colouration of this birds makes it look as though it belongs in more southerly, mediterranean areas, and indeed that is where it seems to do best - probably because there is typically far more rough ground in those countries where the flowers and herbs are just allowed to go to seed, which form the basis of this birds diet. In the UK, we have far less of this type of habitat (it's all too often 'tidied-up') and so there is far less extensive food for the species.

There are a couple of encouraging signs though.... In the last few years, in an effort to reverse the decline in our seed-eating birds, government subsidies have been made available to farmers to plant up areas with mixtures of plant species specifically designed to provide a mix of winter food for the birds - you can often see these rather obviously when out and about, as sunflowers are often a component - and there are already signs that they are helping to some extent. Last autumn I saw a flock of 60+ Goldfinches feeding on just such a strip, and of course they are useful to a range of other species too.

The other thing that is good is that Goldfinches are now increasingly likely to come to food put out for them in gardens. It's a funny thing the way it seems to work, as the general wisdom to attract Goldfinches is that you need a specific type of feeder with a fine mesh that can hold niger seed, and the personal experience of most people that I know who have tried these is that the birds studiously ignore this food (sometimes for a year or more, which is a bit discouraging!) but then they suddenly 'find' them and become regular visitors. Having started to come to your feeders though, they will then often switch their allegiance and start taking sunflower hearts instead. Weird.

It is worth giving it a go though, as Goldfinches seem to act as a kind of 'carrier' species for other, rarer birds in the winter and if you do have a flock of resident Goldfinches visiting your feeders, they are very likely to bring with them some Siskins or Redpolls, and it is a real treat to be able to see these birds up close, instead of the more usual view at the top of an alder tree.

13. Ring-necked Parakeets - psittacula krameri

This is one of those species that is absolutely unmistakable - so if you've ever seen or heard one, you'll know all about it.

It is a medium large bird, but appears larger due to the very long tail and is basically a yellowish-green all over but with a slightly paler head, red bill, black chin and the rosy-coloured collar which gives it its other common name - the Rose-ringed Parakeet. The call is a harsh screech and a large group together can make quite a racket.

You might be asking yourself what a parrot is doing living in SE England and it's not a bad question - there are a number of theories... my own personal favourite is that they were brought to Elstree studios in the 50s to create some atmosphere in a jungle-related film that was being made, and with a fine sense of ecological responsibility, just set free when filming finished! No idea if this is true...

You might think that parrots would struggle to live in our climate and the first bit of inclement weather would kill them off, but this species is native to China where the weather is much harsher than here, and certainly they have done very well. They like to roost collectively and by the 1960s and 70s a very large roost, comprising of several hundred birds had built up at Esher Rugby ground and subsequently they have spread further afield until they are a common sight, not only anywhere within the M25 but also at several other cities throughout the UK. I do think that the release of caged birds probably plays some part, as there are also viable breeding populations of Monk and Alexandrine Parakeets elsewhere in the UK, but the Ring-necked is the one that is most likely to be seen around here.

As a non-native 'invader' this species does provoke some strong feelings amongst the general public and naturalists alike, with some being worried that it will out-compete our own native birds for food and, more particularly, nesting holes. I have to say that I have never seen any evidence of this myself, and the bird that you most often see it squabbling with - the Jackdaw - seems to be doing fine.

Food in the wild is fruit and tree buds, but they do come to bird feeders now and I guess that is where a possible problem may lie - I'm not sure that I'd much like a couple of dozen parakeets descending upon my garden every day and cleaning out my feeders (not to mention decimating my fruit trees!) as they are voracious eaters and do make a heck of a racket. What is for sure is that they are very common now - population into the tens of thousands - and a couple of years ago DEFRA announced that it was permissable for anyone to shoot or otherwise destroy them without any sort of license.

In our immediate local area, they are fairly scarce - I have seen them around the Crowhurst area and also in South Godstone, but it was only in autumn 2011 that they were first reported in the village and the reserve as they continue to spread out from their London base (and not seen since, interestingly enough) but I did hear of one local gamekeeper who said that he will be shooting them, which is quite interesting, as where he is based finding them will be his first problem! They are certainly some considerable way short of being at plague proportions in his particular area but they do like to shoot anything that isn't a Pheasant (until is comes time to shoot them, that is!)

12. Common Buzzard - buteo buteo

It makes a nice change to feature a bird species that is actually a success story, rather than a sad tale of decline, but the Buzzard is one of the species that has been doing really well in recent years. As recently as 10-15 years ago, whilst not unknown, this was quite a rare bird to see around these parts - its stronghold was in the west country, and the further east you came, the rarer the sightings became, whereas now they are a common sight right as far as the east coast and it is not unknown to see groups of 10 or more at one time. Their success is all the more remarkable when you consider that they have a couple of things going against them - they are more-or-less at the top of the food chain so any problems further down will filter upwards to affect them, plus (as birds of prey) they are often a target for ill-informed persecution by game-shooting interests.

They are one of our biggest birds - the largest females having a wing-span of well over a metre - and are just about the largest thing that you are likely to see flying around these parts, with the exception of some geese and swans. Identification amongst raptor species is notoriously difficult but luckily(!) we don't have too many of the other confusion species around here, so you can say with 99% certainty that just about any large raptor that you see will be a Common Buzzard. The only 2 potential species that might trip you up are the Red Kite - which is similar in size but can easily be separated by its deeply forked tail and brighter colouration (I've included a photograph of a Red Kite below for comparison purposes, and also because I rather like the pic!) and the Honey Buzzard, and I won't even attempt to explain the differences between these 2 species - they are subtle and tenuous and I have seen even supposed 'experts' almost coming to blows as they argue whether a buteo species is a Common Buzzard or the much rarer Honey Buzzard.

Luckily, as often is the case, there are a couple of things to help you out with identification.... The best field mark is actually the call, which is a wild, mewing that travels for miles and is often the first thing to alert you to the presence of this species - once you hear it, it is never forgotten and a faint mewing is the signal to start scanning the skies and you will usually be able to track down one or more of them - the call is often given between birds or by one to call another one up from the woods. It always seems to me to be a call that more properly belongs on some wild, wind-swept moorland, and seems very out of place in our gentle Surrey countryside.

The other helpful mark is that all Buzzards have a paler band across their breasts which is plainly visible either in flight or when perched up, so very easy to see. The rest of the plumage and colouration is extremely variable, and not to be relied upon - I know of one experienced and extremely knowledgeable birder who once mistook an very pale morph Common Buzzard which was perched up on a distant bush for an Osprey! .... took me quite a while before I lived that one down!!

Buzzards will eat quite a range of prey - with small mammals, particularly rabbits, being commonly taken, and it may be that the huge recovery in rabbit populations following the myximatosis plague may be key to the success of the Buzzard, but they are not above eating insects and can often be seen on the ground in a wet field hoovering up earthworms - it seems rather out of place to see such a noble bird reduced to such indignities!

As part of my duties for the British Trust for Ornithology, I did an awful lot of surveying of the local birdlife between 2007-2012 and one of the prime purposes of their Atlas survey was to monitor the breeding status of the various bird species in the area. To have something classed as a 'definite' breeding species required quite stringent proof - such as seeing fledged chicks, or adults taking food to a nest etc, and it is to my shame that buteo buteo was a species that I was never able to prove unequivocally bred in this area - I'm 100% sure that they do, I could just never catch them at it!

11. Blackcap - sylvia atracapilla

The Blackcap is one of the most widespread of the summer migrants that come to the UK to breed and also one of the earliest to arrive - often being seen in very early April or even late March if weather conditiions are favourable.

It is a smallish bird - being perhaps slightly smaller than a Robin or House Sparrow and mainly a brownish grey all over with a slightly paler belly. The feature that gives this bird its name is the sooty black cap, but beware, it is only the adult males that have this feature - females have a chestnut brown cap and even immature males do not develop their black caps until into their first breeding year.

They tend to favour woodland and scrubby vegetation and are not always easy to see, having quite a skulking habit but luckily they have one of the best songs which is often the first indication of their presence, being a rich, clear warble which is usually delivered at some volume, so an easy bird to find in a Spring-time wood. Unfortunately there is a confusion species (song-wise) - the Garden Warbler, and the 2 songs can sound very similar to each other, particularly as newly-arrived birds like nothing better than to imitate each-other's songs!! Once they have settled down though and are singing 'properly', the Garden Warbler is, if anything, an even better songster, with a more fluting tone (think Blackbird) and a song that goes on and on, bringing to mind water trickling down a mountain stream, whereas the Blackcap tends to sing in fairly short 5-10sec bursts.

An interesting thing has started to happen to Blackcaps in recent years.... They are a summer migrant to the UK, so would usually head back to warmer climes in autumn, but then people started to report seeing birds in their gardens in the winter. At first, it was thought that climate change was just making that small difference to the UK weather that was necessary to allow Blackcaps to start to become a UK resident, but no - subsequent analysis has shown that all of our summer Blackcaps do continue to migrate as previously, the birds that over-winter in the UK are actually migrants from central Europe (Germany, Poland etc) who have started to migrate westwards in order to take advantage of our milder, maritime climate.... milder compared to a frozen Poland at any rate!

The really interesting thing is what is happening to these central European birds.... Some are continuing to migrate south as per tradition and some are coming westwards to us, and despite the fact that this has only been noted for a couple of decades, there are already slight physical differences in (for example) bill physiology, which are starting to develop - the theory being that the 2 groups are starting to adapt so as to suit the different feeding opportunities in the two areas. Who knows, in years to come, they may be so different that it will become necessary to re-classify them as 2 separate species!!

10. Nightingale - luscinia megarhynchos

Perhaps the article should be entitled 'Lament for a ...', since the main reason for writing is to acknowledge the fact that it now seems rather unlikely that 'our' Nightingale will return to the reserve this year. Mind you, in this we are hardly alone, as I have checked another 9 territories in the Lingfield/Crowhurst area and so far have only found 1 of them to be occupied!

Every so often (last done in 1999) the British Trust for Ornithology mobilises its forces and undertakes a massive survey of Nightingales - the idea being to identify and track every singing male in the UK (in reality, only the SE, since they are not really found anywhere else) and volunteers are assigned areas of the country to look after and survey - my area is 4sq km centred around Blindley Heath. I am really lucky, as this is prime Nightingale habitat and I am currently in contact with 5 singing males.

If you are a Nightingale, then 5-star luxury for you would be dense thorn scrub (Nightingales nest near the ground and need the protection) with bare leaf-litter underneath to feed in and preferably some water nearby. All five of 'my' Nightingales are located in exactly such habitat.

However, there are many, many other locations - both in Blindley Heath and elsewhere locally - that are still perfectly acceptable and have held Nightingales in the past, but this year are largely empty. If this situation is being repeated nationally (and most of my local fellow-volunteers have failed to find any Nightingales at all so far!) then this will represent a catastrophic fall in numbers, on top of falls that have been already been noted in previous surveys.

I have seen enough of them to recognise the pattern for local extinctions....

1. You see plenty of birds in all suitable habitat.

2. You only see them in the very best places - this is called contraction back to prime habitat.

3. Even in the best places, you don't see so many

4. You don't see any, anywhere.

Anyway.... Enough gloom already!! Let's talk about the bird.

If you've ever seen a Nightingale, you would probably be surprised at its drab appearance - how can anything that sings so beautifully look so plain! It is a bit bigger than a Robin and a similar warm brown in colouration with a rusty red rump and tail. I was lucky enough to watch one singing from an open perch the other day and they spread their rusty tail wide open in a very attractive way. Most of the time though, they are extremely secretive and the best you will get is to listen to the song issuing from deep cover. Have a listen here

The males arrive in the UK first (usually about April 20th to early May) and sing VERY loudly to establish a territory and try to attract a female when they arrive a week or two later. In addition to the beautul song, they also have a very weird frog-like croak which I hadn't heard before studying the one in the reserve last year.

By the way - now that you know all about Nightingales, you will know that the chances of finding dense thorn scrub alongside running water in Berkely Square are not very high, and you will be able to deduce that it was probably NOT a Nightingale that was singing there - in all likelyhood a Robin, which will often sing at night-time under streetlights.

9. Swift - apus apus

When I was talking about the harbingers of Spring last week and mentioned Swallows and Cuckoos - how could I possibly omit the Swift, particularly as it is probably my favourite of all the Spring migrants and I always get a real kick out of the first time that I hear their screaming cries each year.

First thing that I need to do though is to apologise, as I do not have a decent photograph of a Swift to accompany this article.... Not sure if it is widely understood, but in order to get photographs of a reasonable quality, you need to get within about 10m of the subject bird, and to get within 10m of a Swift is just about impossible! I will include a link to some photographs here, but to get images of that quality you need a good deal of talent for photography and photographic equipment the size of a piece of field artillery - neither of which I possess....Not all of the photographs are of our UK species - the Common Swift - if you hover the mouse over each image it will usually tell you what species they are, but at a quick glance I noticed some Alpine and White-rumped Swifts, as well as a Swallow!

The principal reason why is it so hard to photographs Swifts is due to their most unique feature - namely that they hardly ever land! They will spent almost 100% of their time on the wing and will eat, mate and even sleep up in the air - the only time they ever come to earth is to visit their nests, which are normally inside building roof-spaces, so you can't see them then either. We are very lucky in Lingfield in that we have a colony of Swifts which nest in the church roof - they were undisturbed by the building work last year and fingers crossed that it will be the same this time.

In addition to being impressive flyers, they can also be quite long-lived and I was reading the other day about a ringing recovery of a bird that had first been rung as an adult 16 years previously, so was at least 18 years old at the time of death. Taking into account a typical level of flight activity for this species, it was estimated to have clocked up about 4 million miles during its lifetime - enough to travel to the moon and back 4 times!!

Id for this species is pretty easy - they are normally in groups, their call is a shrill evocative screaming and they are quiet large (significantly larger than the only other potential confusion species - Swallows and Martins) and look very long winged in flight, their whole body looking rather like a curving, scimitar-like blade. If you ever see something that looks a bit like a Swift but a bit bigger and heavier build (and probably chasing a real Swift) it is very likely that you a looking at a Hobby, which is a small falcon that obviously likes to make life difficult for itself, as Swifts are one of its main prey items - Swifts being able to reach speeds of up to 70mph you see....

Like many other sad tales, Swifts are not doing terribly well in the UK and we are lucky to host a sizable colony here - long may it continue. By contrast, you can still see very large groups in other countries and they are particularly accessable due to the fact that they favour buildings for nest sites, so it is not unusual to sit in a town square with an old church in Spain or Portugal and have literally hundreds of Swifts screaming around you at just over head-height - fantastic! At one of our favourite holiday destinations, just such a sight occurs, but with the added bonus that, as dusk falls, the Swifts gradually diminish in numbers as they gain height to sleep, only to be replaced by hundreds of bats!! Even better!!

The Swift is one of the latest of the Spring migrants to arrive, so it would normally be in about a week or so, but in this crazy year when nothing seems to be behaving as it should, it's anybody's guess. Just keep your ears open though - you'll probably hear them before you see them.

8. Cuckoo - cuculos canorus

I guess that, along with the Swallow, this species is recognised as one of the principal signals of the UK Spring and Summer, but unlike the Swallow, the Cuckoo is suffering quite badly with numbers declining significantly in recent years. I do quite a lot of survey work for the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and before moving to Lingfield, my home patch was the 100sq km which stretched northwards from a line between Nutfield and Hurst Green, and there were no credible records noted in that square for the last 7 years. In my current patch - which is the 100 sq km heading south from that same line (so going as far S as Dormansland and Gatwick airport) I have had a handful of records each year, but there is every indication that this species is contracting back to prime habitat, which means that it is likely that they will vanish from this area too.

In terms of appearance, the Cuckoo is a large, long-tailed bird which when seen in flight, looks rather like a bird of prey - perhaps bringing to mind a falcon (Kestrel?) or maybe a slim accipiter (male Sparrowhawk?) but it is by the call that this species is best known and identified. A certain amount of care is needed though, when identifying this species by call, since I have heard people incorrectly call 'Cuckoo' when they are actually hearing a Collared Dove! The difference is fairly plain though - the Cuckoo is a more staccato call, rising in in inflexion during the first syllable and falling during the second (cuck-oo) whereas the Collared Dove is a more even, gentle, slightly purring call (coo-coo) although not as purring as the Turtle Dove - another local extinction....

If you do hear a Cuckoo, that is the time to look around, since in my experience they will very often call either in flight or at take-off or landing at a new location.

Another feature of the Cuckoo's life-style is that they do not build nests of their own but instead parasitise other species - Meadow Pipits, Reed Warblers and Dunnocks being favoured victims, depending upon habitat, and the female will identify a host nest, eject an egg and replace it with one of her own, which have evolved to closely resemble those of the host species. The Cuckoo chick will normally hatch out earliest, and the young Cuckoo hatchling will then eject any other eggs from the nest, so that the poor parent birds can devote their entire efforts to feeding this imposter, which very soon comes to be far larger than the host adults.

Job done, the adult birds then return to Africa, often being one of the earliest species to start their return journeys, although very recent research has shown wide variations in this behaviour.